On Being Compassionate

WHAT DOES IT REALLY MEAN TO BE COMPASSIONATE?

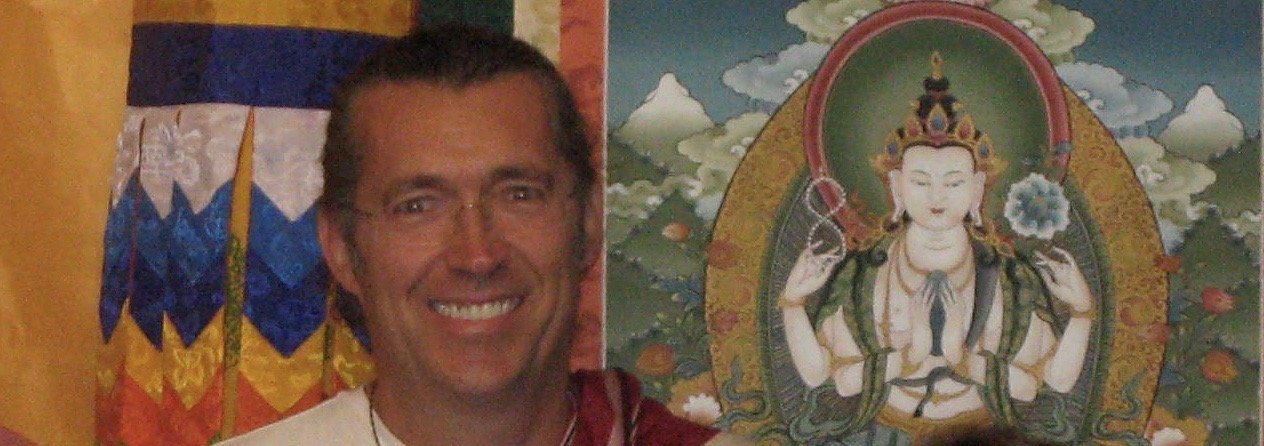

From within all faith traditions, compassionate living and actions are seen as gateways to our highest values and principles in being humans. His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “My religion is kindness.” How does kindness form the basis for compassionate actions? While all of us may say, “Oh I’m compassionate,” the emerging sciences on kindness and compassion reveal the altruistic layers we must peel back in order to touch the core of compassion. Developing kindness is one of those layers, being intimate with suffering without shutting down or turning away is another, and fostering self-compassion, a challenging and difficult one for many, is a third.In training those professionals in the Healthcare and End-of-Life fields, or to any one, I am acutely aware of the most challenging aspect of compassion, which is to remain loving, open and present, especially when we may be experiencing a strong reactive emotion, like anger, or when we feel “triggered” in a given situation. For our heart to remain open and present, the first skill, and really the last skill in any moment, is mindful awareness. Without mindfulness, we can easily fall into less conscious states and habits. We go automatically into reactions to certain behaviours in others from old and even predictable places. Without mindfulness, I believe, we are unable to slow down our emotions or our thoughts. First step: pause, slow down, and ground yourself, then perhaps you turn towards difficulties with compassion.How? With the acronym P.A.U.S.E. (Pay Attention Use Sensory Experiences), that I use in training, it reminds us how mindfulness grounds us into the felt sensations of breathing itself, of the body (i.e., how we are walking, standing, our shoulder tension, or the act of changing an I.V., etc.), and our awareness of hearing sounds, seeing sights, smelling scents, and so on. The experience of mindful pausing stops the “train of thoughts” and brings our attention back to the station (the moment), or from wherever our thoughts and emotions would otherwise travel unheeded. And when we are triggered, we need a powerful and compassionate tool in transforming the suffering that stems from these reactive states.Once we have ‘de-escalated’ our emotional spike, then what? How can I be more kind to my own reactions or to those in another? If we consider the balance we need in riding a bicycle, then mindfulness is the first part of that balancing act. And kindness and compassion is what we are steering towards, rather than driving our relationships into a ditch or a collision, where everyone may get hurt. When we slow down through mindfulness, we are using the second skill of mindfulness known as insight or receptive awareness. Here, we begin to notice the tight knot in our belly or the pulling and tightness around our heart and chest area, or a judgmental thought that comes with difficult encounters with a certain somebody. Most of us may by-pass these kinds of inner awarenesses, because they can be painful, distressing, uncomfortable, or even difficult to control. So, naturally we look for ways to avoid them. This strategy makes senses on one level, as we escape the strife, but what it also does is build up unhealthy responses to difficulty that over time may just make things worse.With practice, we learn to be with the qualities present in our moment-by-moment experience, and then with more curiousity and perseverance, we learn to touch into the roots of a reactive emotion or a strong trigger that sets us off into fear, sadness, jealousy, or rage. Slowing down brings us greater awareness of these states and, through this first skill of mindfulness, we learn that we can let them go in any given moment. This gradually brings us ease, acceptance and greater trust of emotionally states. This is not control, but rather what in neuroscience is called “regulation.” But how to we understand the roots of our emotions and even transform those old prickly triggers? How do we direct compassion and kindness to our own reactions and suffering? This is where your meditation cushion hits the pavement.Buddhist philosophy, drawing upon the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha, explores the foundational teachings about the “truth of suffering.” This truth, or “dharma,” suggests that suffering has many causes and conditions. Ultimately, what we are doing, if our practice is successful, is learning how to “free” ourselves from those causes, from the sources that set off painful states. A “buddha” may simply be someone who has achieved this kindness or freedom from those sources that lead to suffering. In simple everyday ways or as professionals working in the face of crisis, suffering and life and death, we are exposed to many complex conditions and situations that can cause us to suffer. Outer causes such as social, familial and political causes is one source that can cause us to suffer: our patient’s suffering or bad behaviour towards us, a family member’s grief or rage, our co-worker’s rough edges, the structural power issues of working within complicated institutional systems, or the real time challenges of living in a post-Trump era. We can see each of these as “outer” conditions that we face everyday, like rush-hour traffic or getting a speeding ticket because we were caught over the limit.The research suggests, though, that while we may naturally feel compassion towards others, we are limited to the extent of that caring, by our own inner states. In other words, by being more kind and compassionate towards our own “inner” causes of suffering, then our caring may extend with greater resilience towards others. Let’s call this “healthy compassion” where our caring serves others without draining us.So what are the inner sources of suffering? While many of us rarely think of how our early losses or difficult childhood experiences might become the “causes” of today’s reactions and sufferings, the roots of many of our conditioned habits originate from our earliest experiences, from the “child” within us. Without understanding about this child, who lives inside us, without offering kindness to those states within, where we may have felt unlovable, judgmental or shameful, then we may always repeat the same behaviours over and over again, regardless of the situation. Being kind towards the child inside may seem unreal or silly or unnecessary, but if look closely at most “bad” behaviours by the leaders of the world or by you and me alike, they’re not coming from adult places. They’re coming from old childishness and habits that often arise from our unmet needs that truly needed kindness, love and compassion.Thich Nhat, Hahn, a renowned Zen Buddhist teacher, suggests that within each one of us is “wounded” Inner Child. In his article, Healing the Child Within, he suggests that each of us has a child within that has experienced hurt, sorrow, neglect, anger, and fear, and most often these feelings were felt without any kindness, compassion or support. Working with this notion of “childhood” imprints, I believe we can learn to touch the roots of kindness towards that child, which are best understood and felt through kindness practices, such as contemplating “undefended love.” We know this experience of undefended love when we think about being with a child or grandchild, or when imagine the love we feel towards our beloved pet. This love is boundless and unconditional; everyone deserves this quality of love, and few truly know it within themselves. This kindness is the first aspect of compassion that opens the heart, known sometimes as grandmotherly or motherly love. Another aspect of this lovingkindness is felt through contemplating the quality kindness we have felt from a mentor, a grandparent or a dear friend, someone who was present for us and was unconditionally kind to us at a time we needed guidance, tenderness or support. (In the very near future, we will have both of these practices available on our website in the Resource heading, under Guided Practices)In his Compassion Cultivation Training at UCLA, developed by Thupten Jinpa, he outlines the latest research that suggests that those with high self-compassion quotients are more able to receive care and support from others. What this research suggests is that the more self compassion is present in individuals, the more resilient they are. How can we sustain this quality of kindness and compassion, when we keep falling into reactive or defended states? And then how do we extend this compassion towards others? His latest book, A Fearless Heart: How the Courage to be Compassionate Can Transform our Lives acts as an excellent resource for any one wishing to understand the practices of kindness and compassion and the latest research.To me our Mindfulness + Compassion Training Program for Healthcare and End-of-Life Care professionals offered in collaboration with the Mindfulness Project at SickKids is the best way I know to give caregivers the necessary support to not only develop mindfulness, but also to open the doors of kindness and compassion. Through the training, we begin to see the vastness of compassion, where we see that “just like me” everyone has these causes that bring suffering and also too they wish to be free. Through practicing compassion, we can learn new skills in transforming old ways that bring greater peace, ease and well-being into our everyday lives. We can learn to pause more and even to listen to child within us calling for us to listen and see when our old wounds have been touched. Here compassion and kindness may be the balm that heals and transforms.With Kindness, Rev. Andrew